LHA AIR AMPHIBIOUS MISSION

SAIPAN’s air amphibious mission was to land ashore elements of a Marine Corps landing force in an assault by helicopters. The emphasis was on vertical launch and landing of troops and equipment.

This mission was accomplished by the embarkation on a general purpose amphibious assault ship, the LHA, of a Marine Corps Composite Helicopter Squadron.

There were four classes of Marine Corps helicopters embarked on SAlPAN including: CH-53, CH-46, AH-1T, and UH-1N.

The CH-53 “Sea Stallion” was the Marine Corps primary cargo carrying helicopter used for offloading cargo, trucks, jeeps and trailers, and the transporting of essential field gear and C-rations. It could also carry 36 troops with all combat gear.

The CH-46 “Sea Knight” had as its mission the embarkation of troops. It had the capability to carry between 15 and 22 troops with all combat gear.

The AH-1 T “Cobra” was the Marine Corps attack helicopter and was an armed, combat-ready helo that carries one 20mm gun that could fire 750 rounds per minute in Its “mobile turret.” It was also capable of carrying 76 2.75 “Willie Peter” rockets on its ordnance racks. It was the most maneuverable of the helicopters aboard SAIPAN.

The UH-1N “Huey” was the Marine Corps reconnaissance and communications helo, serving as the command post during combat operations. The Huey could also transport demolition teams (UDTs) into the combat zone.

SAlPAN was capable of handling 35 helos aboard during deployment. She couldn also handle 8 of the Marine Corps “Harrier” (jump jet) vertical takeoff and landing jet attack aircraft.

The Marine Corps Composite Helicopter Squadron brought its own maintenance team aboard. The spaces required were previously designated for the squadron. However, SAIPAN’s Aircraft Intermediate Maintenance Department (AIMD) assisted the Marines in logistics support and supply as well as providing direct maintenance support for the embarked aircraft.

There were 10 landing spots on the flight deck and two aircraft elevators. Maintenance was performed in the Hangar Bay located one level below the flight deck. Eight refueling stations could reach all the landing spots on the flight deck. SAIPAN could carry up to 400,000 gallons of jet fuel.

SAIPAN’s air department, consisting of 110 men and headed by a Navy Commander, the “Air Boss,” directed all flight deck operations from the ship’s Primary Flight Control (PriFIi), including landing and launching aircraft, fueling and moving aircraft from the flight deck to the hangar bay and from the hangar bay to the flight deck.

Once aircraft were launched they were controlled by the ship’s Air Operations Officer from the Helicopter Direction Center (HOC). HOC used radar to route the helos to and from the beach for troop delivery at various landing zones (LZ’s). HOC also provided instrument approach facilities, including Carrier Controlled Approaches (CCA’s) for recovering aircraft during bad weather and low visibility conditions.

Next Page: LHA Combat Systems

© Copyright 2017-2022 BelleAire Press, LLC

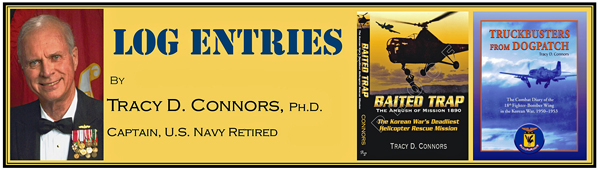

Works by Dr. Connors

Log Entries, are as varied as the person reliving them–interesting, exciting, provocative, stimulating, appealing, heartwarming, lively and entertaining–worth telling to a larger audience, sharing with others some unforgettable experiences and preserving precious memories for future generations.

Truckbusters From Dogpatch: the Combat Diary of the 18th Fighter-Bomber Wing during the Korean War, 1950-1953. The incredible story of the men—pilots, ground crew and supporting elements—whose achievements and records during that bloody conflict not only made U.S. Air Force history, but helped the newly fledged military service gain the confidence and respect it now enjoys.

Baited Trap: the Ambush of Mission 1890. After more than fifty years, we know the riveting story — “…a story that has not been told, but should have been” (Graybeard Magazine) — of the Korean War’s most heroic–and costly, helicopter rescue mission. It took declassification of official records, extensive research, tracking down the scattered families of brave airmen, and use of the Freedom of Information Act, to piece together the story of what five incredibly determined Air Force and Navy pilots did that long June afternoon in the infamous “Iron Triangle.”